In an era where the consumption of mythology often collapses into facile moral binaries or chauvinistic reinvention, the works of Devdutt Pattanaik offer a strange dissonance. His oeuvre straddles the line between the devotional and the academic, the accessible and the arcane, the graphic and the philosophical. Yet beneath this populist appeal lies a deeper logic, a structural grammar of myth that reflects not only the stories we tell ourselves, but the unconscious cultural scaffolding upon which those stories are built. His writing is not just mythography; it is mythopoeic interpretation that unearths how societies use narrative to construct legitimacy, order, and identity.

What follows is a survey and critical reading of five of Pattanaik’s most resonant works not simply the most popular, but the most ideologically and aesthetically compelling. In each case, we find not just a book, but a cartographic act: mapping desire, power, and meaning across the Indian metaphysical terrain.

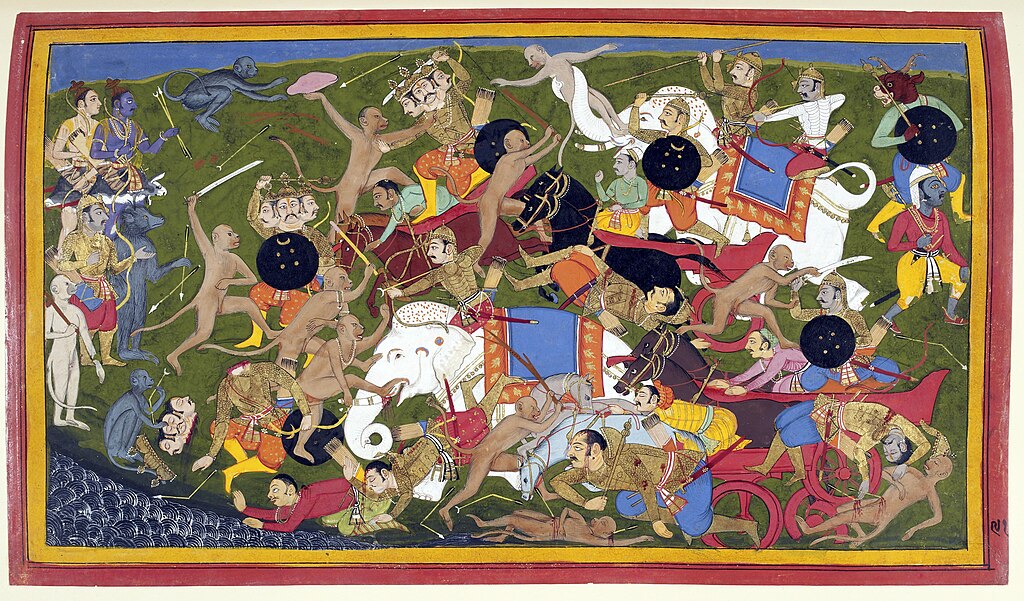

1. Jaya: An Illustrated Retelling of the Mahabharata

At first glance, Jaya appears to be a lush, simplified retelling of the Mahabharata, interspersed with vibrant illustrations and bite-sized interpretations. But its true power lies in its intertextuality: it does not treat the Vyasa Mahabharata as monolith, but rather as a constellation of stories from across regional, folk, and oral traditions. Every footnote becomes a rupture, an acknowledgment of multiplicity that destabilizes the very idea of a singular, “canonical” epic.

Critical Analysis:

Jaya functions less as a narrative and more as an epistemological intervention. By foregrounding alternative tellings (e.g., tribal or Jain versions), Pattanaik undermines any nationalist attempt to weaponize the epic as a monolithic scripture. This is myth as polyphony, not ideology. The text resists closure it fragments, annotates, meanders. And in doing so, it reveals the Mahabharata not as a fixed text but as an evolving cultural organism.

The tension between dharma (social order) and adharma (chaos) is shown not as moral polarity, but as a dialectic of human anxiety.

2. Sita: An Illustrated Retelling of the Ramayana

This work, like Jaya, relies on a blend of narrative fluidity and visual annotation. But Sita is less expansive than its Mahabharata counterpart, and more focused, even meditative. It tells not just the story of Rama but re-centres Sita as the epistemic axis. The silent, interpretive subject through which we understand the cost of heroism.

Critical Analysis:

Where traditional retellings glorify the masculine ideals of duty and kingship, Sita interrogates the sacrificial logic embedded in these ideals. The book becomes a lens to examine how patriarchal structures are legitimized through the performance of ideal womanhood. But crucially, Pattanaik does not paint Sita as a modern feminist rebel, she is a liminal figure, negotiating power through endurance rather than opposition. The ideological work here is subtle: it reframes Sita not as submissive but as radical in her interpretive agency, her refusal to conform to the logic of conquest or revenge.

The Ramayana, as presented here, becomes a text about the costs of divine masculinity. Rama is less hero than function, Sita, less victim than exegete. The result is a critique not only of patriarchal ethics but also of the very narrative structures that perpetuate them.

3. My Gita

A nonlinear, deeply interpretive approach to the Bhagavad Gita, this book refuses chronology and instead structures itself around thematic chapters. Each chapter is a prism, refracting the metaphysical concerns of the Gita through ideas such as liberation, action, detachment, and divinity. It is not a translation it is a reconstitution.

Critical Analysis:

My Gita is perhaps Pattanaik’s most overtly philosophical work. By removing Krishna from the pedestal of theological authority and reimagining him as a conceptual framework, Pattanaik offers a post-structural reading of the Gita itself. The book treats the Gita not as a metaphysical imperative, but as a dialogue with multiplicity. Karma becomes not duty but design; moksha, not escape but understanding.

The text resists totalization. It does not attempt to explain the Gita for all readers but foregrounds its own subjectivity (“My Gita”)an honest recognition that all readings are positional. In doing so, it strips the Gita of its dogmatic veneer and reveals it as a text of deep existential experimentation. The critical move here is deconstructive: dismantling the Gita as law and reconstructing it as lens.

4. Devlok with Devdutt Pattanaik

This is Pattanaik in his most populist mode myths made digestible, accessible, almost modular. Yet the tone never descends into triviality. The Devlok series turns each episode into a mini chapter that bridges the ancient with the contemporary, often with startling insight.

Critical Analysis:

While lacking the textual density of his epics, Devlok reveals another of Pattanaik’s interventions: the democratization of the sacred. It is here that one sees mythology repurposed as public pedagogy. The series strips away Sanskritic elitism and places myth in conversation with daily life, gender roles, ethics, politics, even corporate behaviour.

Yet, despite its simplicity, the ideological terrain remains complex. There is an unspoken critique here of both colonial rationality and modern fundamentalism.

By showing how even gods can be contradictory, insecure, or playful, Pattanaik destabilizes the Western expectation of divine perfection, and simultaneously, the Hindutva urge for sanitized, hyper-masculine iconography.

5. Shikhandi: And Other Tales They Don’t Tell You

This is Pattanaik’s most subversive text. It collects narratives around gender fluidity, queerness, and ambiguity from across Indian mythology. Each story is annotated with commentary that links it to larger philosophical and cultural insights.

Critical Analysis:

Shikhandi is where the ideological stakes of Pattanaik’s work are most pronounced. This is myth used as critique of colonial morality, of binary gender logic, of religious ossification. But it does not impose a modern queer lens anachronistically. Rather, it excavates how Indian mythology has always encoded gender as spectrum, desire as porous, and identity as negotiated.

The ideological move here is not to “liberate” mythology but to remind readers that it was never imprisoned to begin with. The stories destabilize not only Western binaries, but also the sanitized, conservative imagination of “Indian culture” propagated by mainstream institutions. There is a quiet insurgency in this book a refusal to let the sacred be tamed by ideology.

Final Thoughts: Myth as Counter-History

Devdutt Pattanaik’s greatest contribution lies not in myth retelling, but in myth re-seeing. He does not reimagine characters; he reorients the reader. Each of his works, in its own way, resists the flattening logic of singular truth be it religious, moral, or cultural. His myths are not origins; they are mirrors. They do not tell us who we were but ask us what we believe and why.

To read Pattanaik is to be reminded that mythology is not history’s poor cousin it is history’s shadow: irrational, contradictory, and yet profoundly revelatory.

His books do not offer answers. They render visible the very frameworks through which we come to desire answers in the first place. And in that act of rendering visible, they do something even rarer, they restore myth to its rightful place: not as doctrine, but as dialogue.