Why Henry VIII Still Rules the Silver Screen : Reign and Repeat

There are two things you can rely on in this world: the sun will rise in the east, and someone, somewhere in Hollywood, is writing a new script about Henry VIII. Every few years, like clockwork, the corpulent Tudor is dragged out of his historical crypt, powdered and padded, and paraded across our screens with yet another suspiciously handsome jawline. He is played by everyone from Charles Laughton to Jonathan Rhys Meyers, all of whom have precisely nothing in common with the gouty monarch except perhaps a fondness for mood swings and velvet doublets. And one can’t help but ask, in the spirit of weary incredulity: why this man? Why are we so hopelessly enthralled by a bloated tyrant with the emotional stability of a malfunctioning espresso machine?

It’s not just that Henry VIII is fascinating though, admittedly, he is. It’s that he taps into something far more primal: our collective psychological kink for chaos in a crown. Henry is the monarch as psychodrama. He is history’s most flamboyant example of unchecked male ego, spun out to its grotesque conclusion. To borrow the parlance of a therapist, he had boundary issues. And abandonment issues. And power issues. And, quite possibly, a raging case of narcissistic personality disorder, complicated by sexual paranoia and a deeply Protestant inferiority complex. He is Oedipus meets Trump, via Machiavelli, in tights.

Hollywood loves him not in spite of this madness, but because of it.

In fact, if Henry had ruled with quiet competence, limited his marital adventures to one wife, and refrained from inventing an entire national religion just to get a divorce, we’d have forgotten him entirely. But he didn’t. He raged. He loved. He murdered. He sobbed into his roast swan and rewrote the English constitution in the same week. And that, my dear viewers, is what we call character development.

But the Henry-industrial complex is not powered by screenwriters alone. There is something deeper at work something festering in the collective Western psyche. Henry represents, in many ways, the ultimate fantasy of control. In an age where even the most unhinged billionaires must feign moral responsibility, Henry stands as a monument to the idea that power means never having to say you’re sorry. He marries, discards, and decapitates women with the grim efficiency of a man updating his iOS software. He shatters institutions not to make a point, but to silence one. And we watch with horrified delight because somewhere, deep in the lizard-brain, we too long to smash the system with such divine petulance.

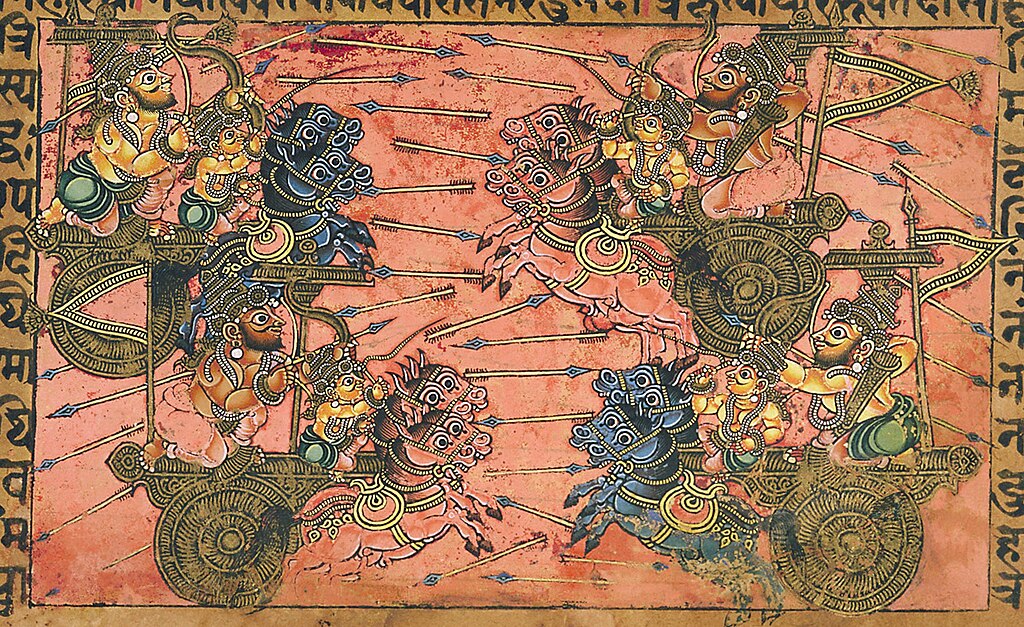

And then there’s the wives. Six of them, neatly categorised into an almost nursery-rhyme formula of fate: divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, survived. It is a chronology so perfect in its grotesquerie, it might have been written by Tim Burton. No wonder filmmakers can’t resist it. The narrative is built-in, the arcs are operatic, and the stakes, love, death, legacy are always absolute. Each wife becomes a psychological mirror to Henry’s unravelling: Catherine of Aragon, the Catholic conscience; Anne Boleyn, the libido; Jane Seymour, the fantasy of innocence; Anne of Cleves, the misfire; Catherine Howard, the return of lust; Catherine Parr, the quiet exhaustion of a man too fat to chase ghosts anymore.

This is not history. This is theatre. Shakespearean, certainly. Freudian, unquestionably.

Every Henry film is a dreamscape of father-hatred, sexual insecurity, and male terror in the face of female intelligence. It is no accident that the most enduring Henry narratives centre on Anne Boleyn sharp-tongued, brilliant, and ultimately too clever to live. In her, we see the limits of charm and beauty when they collide with a man who wants obedience more than love. And when she dies (always in slow motion, always in silence), we are reminded that beneath the spectacle, these are not just courtly intrigues but repetitions of a grim human pattern: the fear of being outwitted, outloved, outlasted.

But perhaps the real reason Henry won’t die is because he never got what he wanted. All this carnage, all this chaos, for what? A son who died young. A throne that passed to two daughters. A legacy that sputtered and was repackaged into costume dramas and pub quizzes. He is the tragicomedy of toxic masculinity made flesh: a man who burns the world for a crown and finds, in the end, that even that won’t stay on his head. He becomes, in his decline, a symbol of all our modern tyrants, those who mistake destruction for achievement, who cannot differentiate between desire and destiny.

So Hollywood returns to him, again and again, like a dog to a particularly scandalous bone. Because Henry is not just a man. He is a mood. He is the dream of freedom twisted into the nightmare of dominion. He is the monarch who thought he could remake the world in his image, and instead remade himself into a cautionary tale with good lighting and better cheekbones.

And we, absurd creatures that we are, still can’t look away.