Introduction

From the earliest oral traditions whispered around flickering campfires to the intricate narratives spun across digital screens, one figure consistently stands at the heart of human storytelling: the hero. Whether a god-like warrior, a cunning trickster, a virtuous saint, or a deeply flawed everyman, the hero archetype permeates every culture and every era.

But why does this figure persist across centuries, undergoing countless permutations yet remaining instantly recognizable? The answer lies in our fundamental human need to confront adversity, to seek meaning, and to project our highest aspirations and deepest fears onto characters who undertake journeys both extraordinary and profoundly relatable.

The evolution of the hero in literature is a fascinating mirror to humanity’s changing values, anxieties, and understanding of the self. What constituted heroism in ancient Mesopotamia differs significantly from modern interpretations, yet threads of courage, sacrifice, and transformation connect them all.

This journey from the god-like figures of ancient myths to the complex, often reluctant saviors of contemporary fiction is a testament to literature’s power to reflect and shape our collective consciousness.

This article will embark on an extensive exploration of the hero archetype, tracing its development across diverse literary traditions and historical periods. We’ll examine how the hero archetype manifests and transforms across cultures, from its mythological roots in ancient epics to its nuanced portrayals in modern literature. We will delve into:

- The foundational figures of ancient mythology and their enduring impact.

- The shifting ideals of heroism during the medieval and Renaissance periods.

- The emergence of the Romantic antihero and the morally complex Victorian protagonist.

- The profound redefinitions of heroism in the existential and disillusioned landscape of the 20th century.

- The diverse, often flawed, and deeply human heroes of postmodern and contemporary fiction.

- Finally, we will analyze the pervasive influence of Joseph Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey” as a universal template for heroic narratives.

By understanding the transformation of the literary hero, we gain deeper insights into the enduring power of storytelling and the ever-evolving nature of the human spirit.

Mythological Origins: The Dawn of Heroism

Long before written language, the heroic narrative existed in oral traditions, passed down through generations. These early heroes were often demigods or mortals blessed with extraordinary strength, divine favor, or exceptional cunning. Their stories, embedded in the very fabric of ancient societies, served multiple purposes: they explained the inexplicable, codified moral and societal norms, and provided figures for emulation and inspiration. These are the foundational literary heroes and mythological roots.

Consider some of the most influential figures from early mythology:

Gilgamesh (Ancient Mesopotamia): Hailed as arguably the earliest surviving work of literature, The Epic of Gilgamesh introduces us to Gilgamesh, a tyrannical king of Uruk, who is two-thirds god and one-third man. Initially arrogant and oppressive, his encounter with the wild-man Enkidu transforms him. Their friendship and joint adventures, culminating in Enkidu’s death, force Gilgamesh to confront his own mortality and embark on a desperate quest for immortality.

While his quest ultimately fails, Gilgamesh returns to Uruk a changed man, accepting his human limitations and dedicating himself to wise rulership. His journey from tyrannical demigod to a more humble, enlightened king demonstrates a nascent understanding of the hero’s internal transformation and the acceptance of human fate. Gilgamesh embodies strength, courage, and a powerful, though initially misguided, drive, but ultimately represents a hero who learns wisdom through loss.

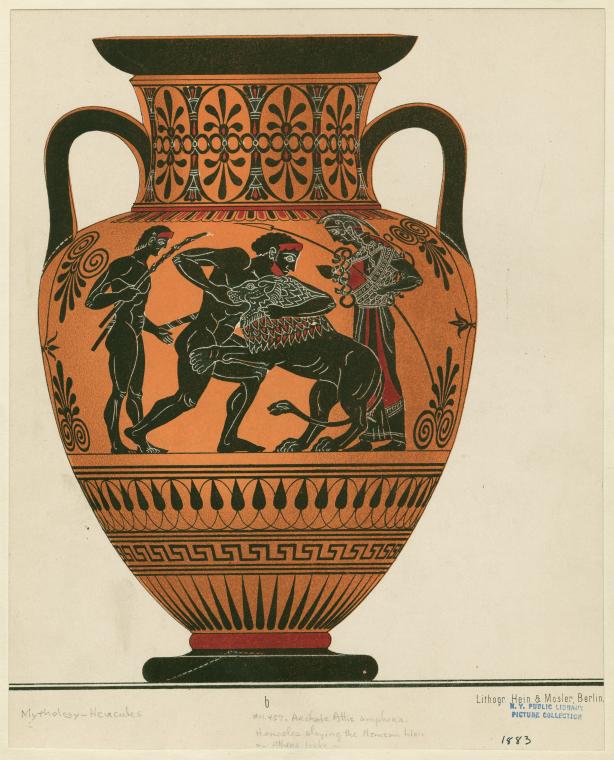

Hercules (Greek Mythology): The most famous of the Greek heroes, Hercules (Roman: Heracles) was the son of Zeus and a mortal woman, Alcmena.

Possessing superhuman strength, he is renowned for his “Twelve Labors,” a series of seemingly impossible tasks imposed upon him as penance for killing his family in a fit of madness orchestrated by Hera. These labors, which include slaying the Nemean Lion, cleaning the Augean Stables, and capturing Cerberus from the Underworld, highlight his physical prowess, immense endurance, and willingness to atone for his sins.

Hercules represents the strongman hero, whose primary virtue lies in his physical ability to overcome overwhelming odds and monstrous foes. Yet, his story also carries a tragic undertone, emphasizing his struggles with divine wrath and his own flawed human nature.

Odysseus (Greek Mythology): Unlike Hercules, Odysseus, the protagonist of Homer’s Odyssey, is celebrated not for his brute strength but for his cunning, intelligence, and eloquence.

A king of Ithaca and a central figure in the Trojan War, his ten-year journey home after the war is fraught with perilous encounters with mythical creatures, tempting sorceresses, and vengeful gods. Odysseus’s heroism lies in his strategic thinking, his resourcefulness, his perseverance against overwhelming odds, and his unwavering desire to return to his family and kingdom.

He is the archetypal “man of many twists and turns” (polytropos), a hero whose greatest weapons are his mind and his words. His journey is one of endurance, cunning, and eventually, the restoration of order.

These mythological heroes, though distinct, share fundamental characteristics that would define the archetype for millennia: exceptional abilities (physical or mental), a journey (often fraught with danger), confrontations with adversaries (human, monstrous, or divine), and a quest for a greater purpose (immortality, redemption, or homecoming).

Their stories established the basic framework for heroic narratives, providing compelling figures through whom ancient societies explored their values, fears, and aspirations. Their stories laid the groundwork for the continuous evolution of the hero in literature.

Medieval & Renaissance Heroes: Faith, Chivalry, and the Human Condition

The shift from ancient mythologies to the literature of the Medieval and Renaissance periods brought new dimensions to the hero archetype, profoundly influenced by the rise of Christianity, the ideals of chivalry, and a burgeoning interest in humanism. Heroes in these eras were often defined by their faith, their adherence to moral codes, and their capacity for both great virtue and profound moral struggle.

Beowulf (Anglo-Saxon Epic Poem, Medieval Period): As discussed in our previous exploration of national identity, Beowulf is also a prime example of a medieval hero, embodying the values of early Germanic warrior culture. Beowulf is a mighty Geatish warrior renowned for his immense strength, courage, and unwavering loyalty. He travels across the sea to aid the Danes by slaying the monstrous Grendel, then Grendel’s vengeful mother, and finally, as an old king, faces a formidable dragon.

Beowulf’s heroism is rooted in his physical prowess, his adherence to a code of honor, and his willingness to sacrifice himself for his people. He is a protector, a slayer of monsters, and a representation of stoic courage in the face of fate. His battles are not merely physical; they are symbolic struggles against evil, embodying the Anglo-Saxon ideal of a valiant and virtuous leader.

Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy (Medieval Period): Dante Alighieri himself is the protagonist and narrator of The Divine Comedy, an epic allegorical poem that takes him on a journey through Hell (Inferno), Purgatory (Purgatorio), and Heaven (Paradiso).

Unlike the physically powerful heroes of old, Dante’s heroism is intellectual, spiritual, and moral. His journey is one of self-discovery, repentance, and spiritual enlightenment. Guided by Virgil (representing reason) and Beatrice (representing divine love), Dante confronts his sins, witnesses the consequences of human actions, and ultimately achieves salvation.

He is a hero of faith and intellect, whose struggle is primarily an internal one, grappling with theological concepts and the very nature of good and evil. His transformation is spiritual, demonstrating a profound shift in heroic ideals from external conquest to internal purification.

Don Quixote de la Mancha (Miguel de Cervantes, Renaissance Period): Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote (published in two parts, 1605 and 1615) marks a pivotal moment in the evolution of the hero in literature by introducing the anti-hero, or at least a highly unconventional one. Alonso Quijano, an elderly nobleman, goes mad from reading too many chivalric romances and decides to become a knight-errant, rechristening himself Don Quixote.

He embarks on absurd adventures, mistaking windmills for giants and inns for castles, all while adhering to an outdated and impractical code of chivalry. Don Quixote’s heroism is tragicomic; he is delusional, often beaten and ridiculed, yet he possesses an unyielding idealism, a noble spirit, and an unwavering commitment to justice, however misguided. He is a hero of imagination and resilience, whose quest highlights the disjunction between lofty ideals and harsh reality. His story is a poignant critique of romanticized heroism and a celebration of the human spirit’s capacity for dreams, even in the face of inevitable failure.

These heroes reflect the changing societal values of their times. Beowulf champions the warrior virtues essential for survival in a harsh world. Dante exemplifies the Christian journey toward salvation and moral enlightenment. Don Quixote, in turn, offers a more complex, ironic, and profoundly human hero, foreshadowing the psychological depth that would increasingly define literary protagonists in later eras. The heroic journey was no longer solely about physical conquest but also about spiritual pilgrimage and the challenges of perception and idealism.

Romantic & Victorian Heroes: Rebellion, Morality, and the Inner Self

The Romantic and Victorian eras, spanning roughly the late 18th to the early 20th centuries, witnessed significant shifts in the portrayal of the hero. The Romantic period, characterized by an emphasis on emotion, individualism, and nature, often celebrated rebellious figures and the power of personal experience.

The Victorian era, while valuing morality, duty, and social order, also explored the complexities of human psychology and societal constraints, leading to heroes who grappled with internal conflicts and ethical dilemmas.

Lord Byron’s Antihero (Romantic Period): George Gordon Byron, known as Lord Byron, profoundly influenced the concept of the “Byronic hero.” This figure is typically a proud, passionate, and rebellious individual, often marked by a mysterious past, brooding melancholy, and a deep sense of disillusionment. He is intelligent, often charismatic, but also cynical, arrogant, and prone to destructive behaviors.

Characters like Childe Harold from Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage or the eponymous hero in Manfred embody this archetype. The Byronic hero is not conventionally good or noble; rather, his appeal lies in his defiance of societal norms, his intense emotional depth, and his tragic grandeur. This figure profoundly shaped the evolution of the hero in literature, introducing a more morally ambiguous and inwardly focused protagonist.

Jane Eyre (Charlotte Brontë, Victorian Period): Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847) presents a vastly different, yet equally revolutionary, kind of hero. Jane is an orphaned governess who, despite her humble origins and plain appearance, possesses fierce independence, strong moral convictions, and remarkable resilience. Her heroism is not grand or public; it is personal and ethical.

She navigates societal injustices, emotional turmoil, and complex moral choices, consistently prioritizing her integrity and self-respect over material gain or social acceptance. Her journey is one of self-discovery, perseverance, and the assertion of individual conscience against societal pressures.

Jane Eyre is a “moral heroine” whose strength lies in her unwavering inner compass and her capacity for enduring love and forgiveness, even in the face of profound adversity. She redefined heroism for women in literature, proving that quiet strength, moral fortitude, and intellectual depth could be as heroic as any physical feat.

These periods mark a significant turning point in the hero archetype across cultures, moving away from purely external conquests or divine favor towards a deeper exploration of the hero’s inner world, psychological struggles, and moral compass. The Romantic hero challenged societal norms, while the Victorian hero often fought internal battles for self-worth and integrity, reflecting the era’s growing interest in individual psychology and social responsibility.

20th Century Transformations: Existentialism, Disillusionment, and the Flawed Hero

The 20th century, marked by two World Wars, economic depressions, and profound scientific and philosophical shifts, fundamentally altered the perception of heroism.

The traditional, unwavering hero seemed increasingly out of step with a world characterized by absurdity, moral ambiguity, and widespread disillusionment. This era gave rise to new heroic archetypes: the existential hero, grappling with meaninglessness; the tragic hero, undone by circumstances beyond their control; and the deeply flawed protagonist, reflecting humanity’s imperfections.

Existential Heroes (Kafka, Camus):

Franz Kafka’s Josef K. (from The Trial, 1925): Kafka’s protagonist is the quintessential anti-hero of the absurd. Josef K. is arrested for an unspecified crime and spends the entire novel trying to understand the charges and navigate an incomprehensible bureaucratic system. His “heroism,” if it can be called that, lies in his persistent, though ultimately futile, struggle against an irrational and oppressive system.

He is a symbol of the individual’s powerlessness in the face of impersonal forces, reflecting a deep anxiety about modernity and the erosion of individual agency. His journey is one of bewildered endurance rather than triumphant conquest, highlighting the absurd nature of existence.

Albert Camus’s Meursault (from The Stranger, 1942): Meursault is the epitome of the absurd hero. He is emotionally detached, indifferent to societal norms, and commits a murder almost by accident, without clear motive. His “heroism” emerges in his final acceptance of the world’s indifference and his own freedom from the illusion of meaning.

He defies societal expectations by refusing to feign remorse or conformity, embracing the “gentle indifference of the world.” Meursault’s heroism is not about good deeds but about an authentic confrontation with existential reality, however bleak. He is a hero defined by his rebellion against conventional morality and his embrace of a personal, albeit unsettling, truth.

These existential heroes showcase a profound evolution of the hero in literature, moving from outward action to inward philosophical struggle.

Tragic Heroes (F. Scott Fitzgerald):

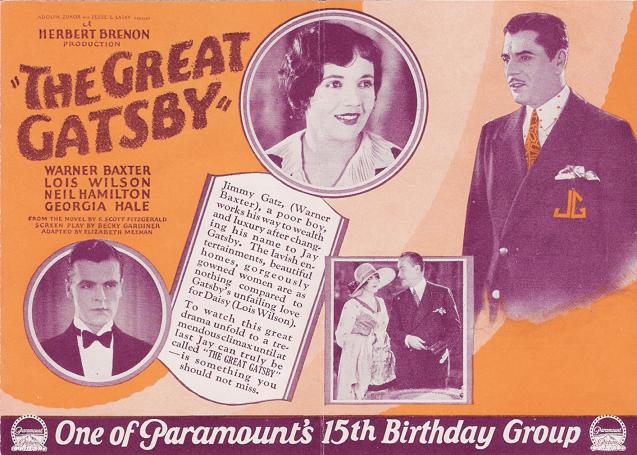

Jay Gatsby (from The Great Gatsby, 1925) by F. Scott Fitzgerald: Gatsby is a uniquely American tragic hero, a self-made millionaire driven by an obsessive, ultimately unattainable, dream of recapturing the past and winning the love of Daisy Buchanan.

His “heroism” lies in his extraordinary capacity for hope, his relentless pursuit of an idealized vision, and his profound innocence amidst the moral corruption of the Jazz Age. However, his tragedy is rooted in the impossibility of his dream and the disillusionment of the American Dream itself. Gatsby’s journey is one of profound aspiration leading to inevitable downfall, not due to a fatal flaw in his character in the classical sense, but due to the inherent flaws of the society and the object of his desire. He represents the hero undone by the very system he tries to conquer or conform to, embodying the disillusionment of a post-war generation.

The 20th-century heroes often reflected a fragmented, uncertain world. They were no longer necessarily strong, virtuous, or triumphant. Instead, they were often outsiders, rebels, or victims, grappling with existential questions, internal conflicts, and the breakdown of traditional values. This era profoundly deepened the psychological complexity of the hero, forcing readers to confront uncomfortable truths about humanity and society.

The Postmodern & Contemporary Hero: Diversity, Reluctance, and the Everyday

The late 20th century and the turn of the millennium brought further fragmentation and redefinition to the hero archetype. Postmodernism, with its skepticism towards grand narratives and its embrace of irony and intertextuality, dismantled many traditional heroic tropes. Contemporary literature, reflecting an increasingly diverse and complex globalized world, continues to explore heroism in nuanced and unconventional ways, often featuring diverse, flawed protagonists, reluctant saviors, and heroes found in the everyday. This era sees the continued evolution of the hero in literature towards greater realism and inclusivity.

Diversity and Inclusivity: Contemporary literature actively challenges the historically dominant heroic archetype (typically male, white, and conventionally powerful) by centering voices from marginalized communities.

Katniss Everdeen (Suzanne Collins, The Hunger Games series, 2008-2010): Katniss is a prime example of a modern reluctant hero. She is not driven by a desire for glory or power but by her fierce loyalty to her family and a desperate will to survive. Thrust into a brutal reality show where children fight to the death, she becomes an accidental symbol of rebellion against an oppressive totalitarian regime. Her heroism stems from her courage, resourcefulness, empathy, and willingness to sacrifice for others, even when she wishes to avoid the spotlight. She is flawed, struggles with trauma, and often acts out of instinct rather than grand strategy, making her highly relatable. Her journey highlights the power of ordinary individuals to catalyze extraordinary change.

Celie (Alice Walker, The Color Purple, 1982): Celie is a powerful example of an everyday heroine who triumphs over immense adversity. Subjected to abuse, racism, and sexism, her heroism is not about physical feats but about spiritual endurance, self-discovery, and eventually, finding her voice and asserting her autonomy. Her journey is deeply personal, yet it speaks to the resilience of marginalized women in the face of systemic oppression. Celie’s heroism lies in her capacity for love, forgiveness, and her ultimate transformation from victim to empowered individual, showcasing a different kind of strength.

Flawed Protagonists and Reluctant Saviors: Many contemporary heroes are far from perfect. They grapple with moral ambiguities, personal demons, and existential doubts. Their heroism often arises from their willingness to act despite their fears and flaws, rather than from an absence of them.

Walter White (Vince Gilligan, Breaking Bad TV series, 2008-2013): While a television series, Breaking Bad offers a compelling, albeit morally ambiguous, modern anti-hero. Walter White, a high school chemistry teacher diagnosed with cancer, turns to manufacturing and selling methamphetamine to secure his family’s future. His journey is a descent into criminality and moral decay, driven by a complex mix of desperation, pride, and a burgeoning thirst for power. Walter is a flawed protagonist whose “heroism” (in the sense of achieving his goals) is intertwined with profound villainy. He challenges traditional notions of who a hero can be, forcing audiences to grapple with the blurred lines between good and evil, and the destructive consequences of unchecked ambition.

The Everyday Hero: In an increasingly complex world, literature also celebrates the heroism found in ordinary acts of kindness, resilience, and quiet courage. These are not figures of epic battles but individuals who navigate the challenges of daily life with integrity and compassion. This shift reflects a societal recognition that heroism isn’t just about grand gestures, but about the human capacity for endurance and ethical choice in ordinary circumstances.

The postmodern and contemporary hero is thus a highly adaptable and diverse figure, reflecting the multifaceted nature of modern existence. They are often defined by their humanity, their struggles, and their capacity for transformation, making the hero’s journey in modern fiction profoundly relatable and continuously evolving.

Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey: A Universal Blueprint

While the hero archetype has clearly undergone significant transformations throughout literary history, many narratives, irrespective of their cultural or temporal context, share a fundamental structural pattern. This underlying pattern was famously articulated by mythologist Joseph Campbell in his seminal work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949). Campbell synthesized countless myths, legends, and religious narratives from around the world to identify a universal monomyth, or “Hero’s Journey.”

Campbell proposed a sequence of stages that a hero typically undergoes, often divided into three main acts:

Part 1: The Departure

- The Call to Adventure: The hero receives an invitation to embark on a quest, often disrupting their ordinary world.

- Refusal of the Call: The hero initially hesitates or declines the adventure due to fear or reluctance.

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero encounters a wise figure who provides guidance, training, or magical aid.

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero leaves their familiar world and enters the special, unknown world of the adventure.

Part 2: The Initiation

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero faces a series of challenges, forms alliances, and confronts adversaries in the special world.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave: The hero prepares for the supreme ordeal, often venturing into the most dangerous part of the special world.

- The Ordeal: The hero confronts their greatest fear or obstacle, facing death or a moment of crisis.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword): Having survived the ordeal, the hero gains a prize or treasure, often symbolic (e.g., knowledge, power).

Part 3: The Return

- The Road Back: The hero begins the journey back to the ordinary world, often pursued by forces from the special world.

- Resurrection: The hero faces one final, ultimate test, often a “death and rebirth” moment, before returning to the ordinary world. This test often purifies and transforms them.

- Return with the Elixir: The hero returns to the ordinary world, bringing with them a “boon” or “elixir” (e.g., wisdom, peace, a solution) that benefits their community or the world at large.

Impact on Storytelling

Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey” has had an immense impact on storytelling across various mediums, from literature to film, television, and even video games. Its widespread influence stems from its ability to provide a flexible yet recognizable framework for creating compelling narratives.

- Universality: It suggests that despite cultural differences, human experiences of growth, challenge, and transformation share deep structural similarities. This makes heroic narratives resonate across diverse audiences.

- Narrative Blueprint: For writers, it offers a practical roadmap for structuring a story, ensuring a coherent arc and satisfying character development. While not all stories follow it rigidly, it provides a powerful foundational understanding.

- Character Development: The journey emphasizes the hero’s internal transformation, showing how they grow and change as a result of their trials, rather than simply being a static figure of strength. This allows for the creation of psychologically complex heroes.

- Commercial Success: Its application is evident in countless popular narratives, from Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings to many modern fantasy and adventure stories. The familiarity of the pattern often contributes to a story’s accessibility and appeal.

While some critics argue that Campbell’s monomyth can oversimplify diverse narratives or impose a Western-centric view, its enduring appeal lies in its recognition of shared human experiences and its ability to provide a powerful framework for understanding the profound and universal nature of the hero’s quest. It remains a crucial tool for analyzing the evolution of the hero in literature and understanding why these figures continue to captivate our imaginations.

Conclusion

The journey of the hero archetype through the annals of literature is a testament to the enduring power of storytelling and humanity’s perennial quest for meaning, purpose, and self-understanding. From the formidable strength and divine connections of Gilgamesh, Hercules, and Odysseus, who embodied the raw virtues and foundational myths of ancient civilizations, to the morally complex figures of Dante and Don Quixote, grappling with faith, idealism, and the nascent complexities of the human condition, the hero has always mirrored the prevailing values and anxieties of their age.

The Romantic era introduced the brooding, rebellious antihero, while Victorian literature explored the quiet resilience and moral fortitude of figures like Jane Eyre, shifting focus to internal struggles and ethical integrity. The 20th century, scarred by global conflicts and existential crises, gave us the alienated, often disillusioned heroes of Kafka and Camus, alongside the tragic figures like Gatsby, reflecting a world grappling with absurdity and shattered dreams. Today, in our postmodern landscape, the hero is more diverse, more flawed, and often more relatable than ever before. From reluctant saviors like Katniss Everdeen to the everyday heroism found in resilience and self-discovery, contemporary literature embraces a kaleidoscopic range of protagonists, challenging traditional notions of power and perfection.

Joseph Campbell’s articulation of the “Hero’s Journey” provides a powerful analytical framework, revealing the universal structural patterns that underpin countless heroic narratives across cultures and time. It reminds us that despite the vast differences in their outward manifestations, heroes consistently undertake journeys of departure, initiation, and return, undergoing transformations that resonate deeply with the human experience.

The evolution of the hero in literature is not merely a historical record; it is an ongoing dialogue about what it means to be human, to face challenges, to make choices, and to find meaning in a perpetually changing world. As long as humanity continues to confront adversity, seek purpose, and wrestle with its own imperfections, the hero, in all their myriad forms, will continue to stride across the pages of literature, reflecting our deepest aspirations and helping us navigate our collective journey.

FAQ Section

Q1: What is a hero archetype in literature?

A1: A hero archetype in literature refers to a recurring character type or pattern of character traits found across various myths, legends, and stories. This archetype embodies universal human qualities and experiences, such as courage, sacrifice, transformation, and the pursuit of a quest.

Q2: How has the hero archetype changed from ancient myths to modern literature?

A2: The hero archetype has evolved significantly. Ancient heroes were often demigods or physically powerful figures with divine favor (e.g., Hercules). Medieval heroes emphasized faith and chivalry (e.g., Dante). Romantic heroes introduced rebellion and psychological complexity (e.g., Byronic hero). 20th-century heroes became more existential, flawed, and often tragic (e.g., Josef K., Gatsby). Modern heroes are highly diverse, often reluctant, flawed, and can be ordinary individuals achieving personal triumphs (e.g., Katniss Everdeen, Celie). This demonstrates the full evolution of the hero in literature.

Q3: What is the “Hero’s Journey” and why is it important?

A3: The “Hero’s Journey,” or monomyth, is a narrative pattern identified by Joseph Campbell that describes a common sequence of stages a hero undergoes in myths and stories across cultures. It’s important because it reveals universal psychological and narrative structures, provides a blueprint for storytelling, and emphasizes the hero’s internal transformation, making it a crucial concept for understanding the hero’s journey in modern fiction.

Q4: Can an anti-hero be considered a hero?

A4: Yes, an anti-hero can be considered a type of hero, though they lack conventional heroic qualities such as idealism, morality, or nobility. Anti-heroes often possess flaws, cynicism, or engage in morally ambiguous actions, but they may still achieve heroic outcomes or prompt readers to reconsider what constitutes heroism. Don Quixote and Walter White are often cited as examples.

Q5: How do cultural values influence the portrayal of heroes?

A5: Cultural values profoundly influence the portrayal of heroes. For example, ancient Greek heroes embodied values like physical prowess and cunning, while medieval Christian heroes emphasized faith and spiritual struggle. Modern heroes often reflect contemporary values of diversity, psychological realism, and individual resilience, demonstrating how the hero archetype across cultures adapts.

Q6: What does it mean for a hero to be “flawed”?

A6: For a hero to be “flawed” means they possess imperfections, weaknesses, or moral ambiguities that make them more realistic and relatable. Unlike idealized heroes, flawed protagonists might make mistakes, struggle with personal demons, or commit questionable acts, yet their journey often involves overcoming or coming to terms with these flaws, highlighting the human element in their heroism.

Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy.

Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. 1847.

Byron, George Gordon. Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.

Byron, George Gordon. Manfred.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press, 1949.

Camus, Albert. The Stranger. 1942.

Cervantes, Miguel de. Don Quixote.

Collins, Suzanne. The Hunger Games. Scholastic Press, 2008-2010.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. 1925.

Gilligan, Vince, creator. Breaking Bad. AMC, 2008-2013.

Grimal, Pierre. The Penguin Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Penguin Books, 1986.

Heaney, Seamus, trans. Beowulf: A New Verse Translation. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000.

Homer. The Odyssey.

Kafka, Franz. The Trial. 1925.

Maier, John. Gilgamesh: A Reader. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 1997.

Morford, Mark P. O., and Robert J. Lenardon. Classical Mythology. 9th ed., Oxford University Press, 2011.

Sandars, N. K., trans. The Epic of Gilgamesh. Penguin Classics, 1972.

Walker, Alice. The Color Purple. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982.