It is always afternoon in Devdutt Pattanaik’s world. The light is golden, caught somewhere

between the lamp of a shrine and the stage of a kathakali theatre. The gods do not thunder

there; they converse, gossip, trade places. Ganesha listens. Shiva waits. Krishna smirks.

When Pattanaik first stepped away from the stethoscope and into the mytho-graphic

imagination of India, the cultural establishment barely stirred. But he was not interested in

establishing anything. His interest was in maps: not just of epic battles and cosmic realms,

but of minds and nations. Myths, he said, are the operating systems of our societies.

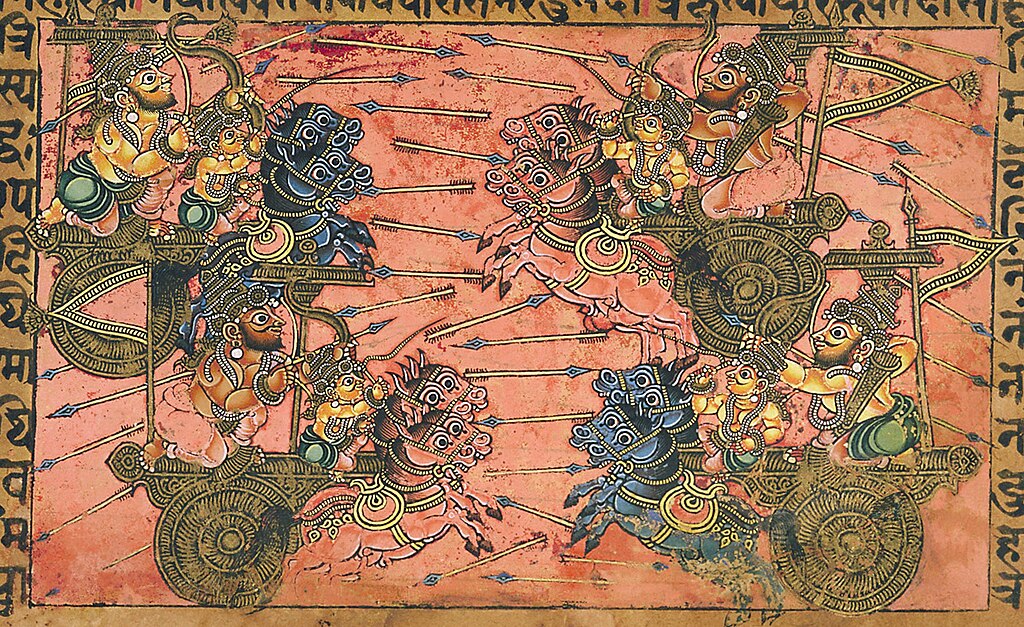

He began not with a revolution but a diagram. Circles, arrows, grids. Myth as infographics.

Ancient stories distilled into modern frameworks. Ramayana, Mahabharata, the Puranas

restructured not with irreverence, but with a clarity that startled. In a country where gods

hang in every roadside stall and mother’s kitchen, he reinstalled them into public discourse.

Yet it was not his knowledge of scripture that drew people in, it was his tone. Like Wilde’s

wraith, he was amused, precise, a little wicked. He once said mythology is not about truth or

untruth, but about what a society believes to be true. The sentence slid into public

imagination like a blade into silk. And there, something shifted.

For too long, Indian mythology had been held hostage by either the zealot or the academic.

Pattanaik offered a third path, accessible, plural, queer. He asked: what if we treated the

gods not as property but as stories? Not fixed idols but evolving ideas?

You could find him in the oddest places. One day on TED, explaining the Ramayana as a

culture of guilt versus the Mahabharata as a culture of shame. Another day, on TV, beside a

winking sage or an over-muscled deity, as he re-narrated the Mahabharata for a nation

watching its own reflection flicker across myth and soap opera.

His books piled up like yajna offerings Jaya, Sita, Shikhandi, My Gita, The Pregnant King.

Each a different gesture, a different question. He did not ask us to believe, only to look.

Even the titles were playful, deliberate. The Pregnant King was a rupture, a provocation.

Could queerness be traced not only in contemporary life but in scripture? Could the binaries

we inherited be stories told one way, when there were other ways?

Like Blake before him dismissed in his time as “too little sane” to be important Pattanaik was

disconcerting to both the orthodox and the rationalist. Too mythic for the academic. Too fluid

for the fundamentalist. Too popular, perhaps, for the elite.

But the ground beneath us was changing.

It is tempting to say that Pattanaik merely re-popularized Indian myth. But that would be like

saying Wilde just wrote plays. What he really offered was permission. Permission to think of

gods as metaphors. Permission to see dharma not as dogma but dilemma. Permission to

imagine a future that did not look like a flag, but a mandala.

He once wrote: “Lakshmi comes to Vishnu not because he is rich, but because he shares.” It

was the kind of sentence that sounds like a proverb until it begins to burn. Sharing is not

charity, he reminds us; it is cosmology.

And the metaphors keep circling: Ravana is not evil, just out of alignment. Krishna is not

divine because he follows rules, but because he breaks them wisely. Shiva dances not to

destroy, but because destruction is necessary for creation.

In his world, myth is not nostalgia, It is software. Gods are not dead they are evolving user

interfaces.

Of course, not everyone was convinced. That was the point. In the post-truth age,

Pattanaik’s version of myth was heretical. He refused to pick a side. He insisted that every

truth was contextual. He quoted the Vedas and Foucault in the same breath.

He did not deconstruct religion. He revealed that it had always been constructed. And this, for many, was the most dangerous idea of all.

For some, he is too pop. For others, too provocative. But to a generation trying to find itself

in the debris of modernity, he became a kind of Virgil guiding not into heaven or hell, but into

the stories that told us who we were, and who we might yet be.

Where does Devdutt Pattanaik stand now? On a threshold, perhaps. Between the ashram

and the airport lounge. Between Valmiki and Vogue. Between the past we forgot and the

futures we have not yet dared to imagine.

In his writings, the gods never leave. They slip between worlds. They change shape. They

return in dreams, movies, corporate trainings, and children’s drawings. They are not calling

us to worship. They are calling us to wake up. It is always afternoon in Devdutt Pattanaik’s

world, and the gods are still talking.

Lateral Reading List: Five Books to Read Alongside Devdutt Pattanaik’s Works

- Roberto Calasso – Ka: Stories of the Mind and Gods of India

o A lyrical, densely allusive retelling of Indian myth that complements Pattanaik’s clarity with metaphysical depth. - Wendy Doniger – The Hindus: An Alternative History

o A scholarly and provocative history that mirrors Pattanaik’s pluralism, but from

a rigorous academic standpoint. - Ananda K. Coomaraswamy – The Dance of Shiva

o Essays that explore Indian aesthetics and metaphysics, grounding Pattanaik’s

intuitive insights in classical tradition. - Joseph Campbell – The Hero with a Thousand Faces

o A global mythic framework that aligns with Pattanaik’s comparative approach

to stories, archetypes, and transformation. - Neil Gaiman – American Gods

o A fictional but resonant exploration of myth in the modern world, echoing

Pattanaik’s treatment of deities as living metaphors.